Religious Life Committee Blog

16 Adar 5783 / 9 March 23

reflections on the work of the religious life committee

As the current board cycle of the Religious Life Committee (RLC) nears end, we reflected on accomplishments and work remaining to be done. When we started on a work plan, we had no idea that in less than a year, COVID would upend plans, ours and everyone’s. Much of the past three years have been devoted to the enormous work of adapting to the challenges of the pandemic, moving services to Zoom, becoming hybrid, and now moving back into physical space. Still, a lot has happened in pursuit of the goals the Committee adopted:

Top of our list was creation of an alternative service as recommended by the Avodah Task Force during strategic planning. The Alternative Service has gone through three iterations, Minyan Shelanu, Minyan Ohalecha, and now a pair of Shabbat variations aimed at sparking interest, renewal and engaging a wider range of CSI members.

The corps of prayer leaders, Torah and haftara readers, has expanded significantly. Not counting new b’nei mitzvah and their family members who perform these duties once, our congregation has benefited from the representation of twelve new haftara chanters, twenty new shelichei tzibbur (emissaries of the community), and a whopping thirty-five new leyners (Torah readers) in the past four years. This has been aided by tefila leadership classes and one-on-one coaching organized by the RLC and by Sisterhood. A new Learners’ minyan has just started, and new leyners chavurah is about to begin. I don’t have a good count of how many new gabbai’im and shamashim we have, but the full group now numbers thirty.

We spent quite a bit of time working with our rabbis to better understand expectations for prayer in our shul, and sharing these expectations with shelichei tzibbur, gabbai’im and shamashim. Among the principles we advocated is the belief that it is better to let a minhag slip by than embarrass a congregant or visitor in front of the community.

Shearith Israel adopted the new Machzor Lev Shalem last year, moving to the Rabbinical Assembly’s 21st Century High Holiday prayerbook that is more gender neutral, offers many aids in navigation, and offers a wealth of commentary and additional readings.

A Tefillin Challenge, funded by the Kornblum Minyan Fund, began which offers phylacteries to any new Shearith Israel bar or bat mitzvah who agrees to learn how to use them and to participate in morning minyan at least ten times the following year.

Each February, CSI joined the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs World Wide Wrap. New themed Shabbatot celebrated new members, new leyners, and Machaneh Shai students. We returned to honoring veteran’s in shul each Veteran’s Day. Friday Night Live services with lay-led drashim and sponsored onegim have drawn a significant following. Other Kabbalat Shabbat and Shabbat evening services have struggled, however.

Daughters of Kohanim offered the priestly blessings for the first time in our shul at Sukkot this year; this following the rabbinic decision that they were welcome to do so. Also following a new teshuva released by the Rabbinical Assembly, we announced that non-binary language may be used to call persons to Torah aliyot when requested.

The passing of a number of minyan regulars and adjustments to Zoom, have meant challenges to keeping up attendance at daily services. Most recently, Rabbi Kaiman announced a campaign to seek at least monthly minyan participation by all congregants who can do so. This is very much a work in progress.

These years have seen a lot of work on ritual objects and spaces. All Shearith Israel’s sifrei Torah were evaluated by a sofer (learned scribe), repairs were made as needed, and registrations with the Jerusalem Torah registry Machon Ot were brought up to date. This process resulted in two sifrei Torah found no longer suitable for use and beyond repair; these have been removed from service.

Medallions to identify the appropriately rolled sifrei Torah to be read on a given Shabbat or Yom Tov were commissioned with a generous donation by the Stein family. A page number display was purpose built for the Sanctuary by Sam Prausnitz-Weinbaum with financial support from the Block family. New book racks and a TV cabinet were designed, built and installed in the Sanctuary and the Chapel. Conversations began about renewing the mantles that dress the sifrei Torah and the embroidered cloths used to cover them and the reader’s table in the Chapel.

RLC has been concerned about Shabbat observance on our campus. We have been working with the Building and Grounds Committee and the Master Planning Committee towards building lighting systems that are properly shomer Shabbat and that will also be more energy conscious.

Some years ago, when I began an NGO leadership post, I was counseled that 80 percent of leadership is keeping the ship on course. To that point, I have to recognize the incredible work done by Michael Rich and Andrea Seidel Slomka, in scheduling the volunteers who make Shearith Israel’s tefilot happen week in and week out; Andrea SS, Michael R, Michael Froman, Al Hazan, Howie Slomka, and Howard Zandman, who are responsible for a great deal of leyning in our full-kryiah practice; Michael F. and Ed Jacobson, who staunchly captain most daily minyanim, and Lynne Borsuk, who champions Friday Night Live. The other RLC-niks, Alex Berg, Sara Duke, Barry Etra, Katie Levitt Green, Melanie Kaplan, Susie Mackler, Sarah Ossey, Edward Queen, Marcia Jacobs, Greg Menkowitz, and Ori Salzberg, each have had a portfolio of project work and are responsible for the results you see here. We are grateful for the support of the shul staff and the Board – in particular, Vice-presidents Michael Rosenzweig and Pia Koslow Frank, whose briefs included the committee. Rabbi Kaiman and Rabbi Helfand, are the driving force behind religious life in our shul.

It has been an honor to serve as committee chair these past four years. I’ve gotten to know many of you through this work, and I’ve deepened my Jewish knowledge. Thank you for your commitment to fostering the success of this kehilla and making it such an enjoyable community.

Michael Rich will stand for election this Sunday as the next RLC chair. His dedication to the religious life of Shearith Israel is wonderful; I know he will steer this committee with vision and sensitivity. Please consider putting your own name forward to join the work.

See you in shul,

Baruch

24 Shevat 5783 / 15 February 23

Preparing Our Loved Ones for Burial

The seventh of Adar, observed as the yarzheit of Moshe Rabbeinu, has become a day for members of the Chevra Kadisha, or holy society that prepared bodies for Jewish burial to gather and discuss their work. In Atlanta, chevrot kadisha from across the region gather on that day. We no longer wear morning coats as they did in Prague in 1772 in this picture; we do include women, good food and interesting speakers.

The seventh of Adar, observed as the yarzheit of Moshe Rabbeinu, has become a day for members of the Chevra Kadisha, or holy society that prepared bodies for Jewish burial to gather and discuss their work. In Atlanta, chevrot kadisha from across the region gather on that day. We no longer wear morning coats as they did in Prague in 1772 in this picture; we do include women, good food and interesting speakers.

Among the many ways to participate in our CSI community is the Chevra Kadisha. The group prepares the body for Jewish burial (Taharah) based on Jewish traditions and customs for our members and at times the greater Atlanta Jewish community. While at first this may seem scary and ominous, many of us find this a very meaningful and holy experience. None of us had ever been involved in this level of observance or had dealt with death in this way. What binds us is knowing our work nurtures and supports the body and soul of the deceased congregants as we prepare the individual for burial with respect, dignity and caring.

Our Chevrot Kadisha are gender based whose members are of varied professional backgrounds, levels of observance and Jewish knowledge. The women’s Chevra Kadisha has 19 active members and the men’s has 20. We remained active adjusting to the multiple issues and challenges of performing Taharot during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. We are back to doing Taharot following our traditions and customs. In 2022 the women performed 15 Taharot and the men 4.

Both Chevrot Kadisha are looking to enlist new members due to our members getting older or having to take on family caregiving responsibilities. We held a joint informational meeting in January for those who were interested to learn more about Taharah and what is involved with no commitment to joining us. We also offered an opportunity to observe a Taharah, again without any commitment. Should anyone be interested in learning more or observing, please contact us.

The painting is one of twelve depicting the Prague Burial Society from 1772 online: https://www.jewish-funerals.

13 Tevet 5783 / 5 January 23

Gender Steps Forward

During the Phyllis Podber, z’l, levaya this past Sunday, Rabbi Kaiman recalled CSI then-Assistant Rabbi Elana Zelony coaching Mrs. Podber in her 80s, so that she could be called to the Torah during her mourning for her late husband, Abe, z’l, and then Mrs. Podber’s satisfaction at honoring Abe in this way. Few Jewish women born in Europe in the early 20th Century imagined that this would be possible for them. Today this is normal in Conservative/Masorti shuls around the world. The goal of gender egalitarianism has a long way to go if it is to be fulfilled in our communities, but 5783 has seen some important steps forward at Shearith Israel.

During the Phyllis Podber, z’l, levaya this past Sunday, Rabbi Kaiman recalled CSI then-Assistant Rabbi Elana Zelony coaching Mrs. Podber in her 80s, so that she could be called to the Torah during her mourning for her late husband, Abe, z’l, and then Mrs. Podber’s satisfaction at honoring Abe in this way. Few Jewish women born in Europe in the early 20th Century imagined that this would be possible for them. Today this is normal in Conservative/Masorti shuls around the world. The goal of gender egalitarianism has a long way to go if it is to be fulfilled in our communities, but 5783 has seen some important steps forward at Shearith Israel.

First, at the beginning of Sukkot this year, in a first for Shearith Israel, three b’not Kohanim and one bat Levi, participated in the priestly blessing ritual (Birchat Kohanim or duchenen) in our Musaf service. The participation of female offspring of Kohanim in the priestly blessing was allowed by the Rabbinical Assembly’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) in 1994 when it approved a teshuva authored by R’ Mayer Rabinowitz entitled Women Raise Your Hands1. It would have been possible for our shul to begin this practice when we moved to egalitarianism in 2004, but for reasons unknown to me, this egalitarian practice was held out while others were adopted.

This past Spring, the Religious Life Committee opened discussion of a change to encourage b’not Kohanim to participate in duchenen, and Rabbi Kaiman endorsed the change. Lara Rodin, a bat Kohein enrolled in the rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Seminary, kindly agreed to instruct b’not Kohanim at CSI, and a Zoom session was held in August. With the participation of b’not Kohanim in Birchat Kohanim on Sukkot I, our community has finally reached the milestone of including women in all ritual practices that are also available to men.

Remaining is the issue of whether, now that it is allowed, is duchenen a requirement for b’not Kohanim? This is an uncomfortable question because the criteria on which answers to this issue are based are largely the same for many other mitzvot, both for women and men, in Jewish halacha. As R’ Pamela Barmash states in a 2014 CJLS teshuva2, “Egalitarianism, the equality of women in the observance of mitzvot, is not just about the participation of women: it is about fostering the fulfillment of mitzvot by all Jews…. In Conservative synagogues, schools, and camps, opening mitzvot to women has led to the implicit assumption that women are equally obligated to observe the mitzvot as men have been and that mitzvot from which women have traditionally been exempted are not only open to them but are required of them.” The reasoning in this important teshuva applies equally to tallit, daily prayer, tefillin, and other mitzvot as it does to duchenen, but critically, the conclusion applies to men as well as women and to such mitzvot as kashruth and Shabbat observance. By the standards of halacha, if we are allowed to perform a required mitzvah, we are obligated to do so, both women and men.

Second, also this year, the CJLS released a teshuva discussing the calling of non-binary persons to aliyot. Rabbis Guy Austrian, Robert Scheinberg, and Deborah Silver hold that it is time to ensure that non-binary individuals are appropriately honored when called to the Torah3. They recommend modifications to the language of the call to aliyot that sidestep the gendered language usually used, including use of the non-gendered verb form, נא לעמד/na la’amod (please stand), in place of 'עמד/תעמד /ya’amod/ta’amod (let ___ stand); and מבית/mi’beit (from the house of), in place of בן\בת/bein-bat (son/daughter of). So a non-binary individual might be called with language such as: נא לעמד נח מבית יעקב ושרה (Please stand, Noah of the house of Yacov and Sara).

The CSI Religious Life Committee discussed this teshuva this fall, and Rabbi Kaiman has ruled that use of non-binary language is permitted at Shearith Israel. Our gabbai’im and shamashim discussed the practicalities in a meeting this past month and there are now instruction sheets with both gendered and non-gendered call forms illustrated on the readers’ tables in both the Sanctuary and the Chapel. We ask that members of the shul who wish to use non-binary Hebrew names enter the non-binary name form in the Hebrew name field in their shul membership listing so that it can be printed on the cards used to call members on Shabbat and Yom Tov. Anyone, of course, could give a non-binary form name to a shamash or gabbai when they are to be called. Rabbi Kaiman and Rabbi Helfand would be glad to assist anyone who is unsure how best to list their Hebrew name.

Lehitra’ot,

Baruch Stiftel

_____________________________________________

1 Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz. Women Raise Your Hands. OH 128:2.1994a. Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, 1994. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/assets/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19912000/rabinowitz_women.pdf It should be noted that a second teshuva, finding that b’not Kohanim should not participate in duchenen was approved by the CJLS (by minority vote) at the same time the Rabinowitz teshuva was approved (by majority): Rabbis Stanley Bramnick and Judah Kogen. Should N’siat Kapayim Include B’not Kohanim? OH 128:2.1994b. Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, 1994. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/assets/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19912000/bramnick_kogen.pdf

2 Rabbi Pamela Barmash. Women and Mitzvot. Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. Y.D. 246:6, 2014. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/teshuvot/1638984477.pdf

3 Rabbi Guy Austrian, Rabbi Robert Scheinberg, and Rabbi Deborah Silver. Calling non-binary people to Torah honors. Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. OH 139:3 2022, 2022. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/teshuvot/1654031435.pdf

22 Sivan 5782 / 21 June ‘22

post-pandemic tefila at csi

At the start of the COVID shutdown in March 2020, Rabbi Kaiman followed the guidance of many Masorti authorities and determined that the she’at hadehak (crisis situation) of the pandemic created an obligation to stop convening prayer in person so as to protect life. At the same time, in the interest of supporting the mitzvot connected with prayer, he authorized us to convene minyanim using new Internet technology, and we began Zoom services. Then, in Elul last year, recognizing that the public health situation allowed many of us to return to in-person davening, with the support of the synagogue board, Rabbi Kaiman reopened our Sanctuary to in-person davening and moved our Shabbat and Yom Tov services to livestream, while continuing to conduct weekday services in Zoom.

At the start of the COVID shutdown in March 2020, Rabbi Kaiman followed the guidance of many Masorti authorities and determined that the she’at hadehak (crisis situation) of the pandemic created an obligation to stop convening prayer in person so as to protect life. At the same time, in the interest of supporting the mitzvot connected with prayer, he authorized us to convene minyanim using new Internet technology, and we began Zoom services. Then, in Elul last year, recognizing that the public health situation allowed many of us to return to in-person davening, with the support of the synagogue board, Rabbi Kaiman reopened our Sanctuary to in-person davening and moved our Shabbat and Yom Tov services to livestream, while continuing to conduct weekday services in Zoom.

As the pandemic retreats and the world around us opens up more and more, we have to determine what prayer will be like at Shearith Israel going forward. Will our prayer rooms continue to be mostly empty, or will our Jews return to the pews? Will we continue to livestream Shabbat and Yom Tov services? Will we continue to conduct hybrid weekday minyanim? Rabbi has asked the Religious Life Committee to explore these questions with our congregation. Preparing for those conversations, today, I want to look at what the Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CLJS) offers as guidance.

The View Before the Internet

The Rabbinical Assembly began grappling with remote participation in davening in the late 1980s, when Rabbi Gordon Tucker held that remote participation in tefila using a monitor and loudspeaker, while far from ideal, should be permitted as a final and unavoidable alternative providing the technology used was not manipulated on Shabbat or Yom Tov by Jews1. While R’ Tucker’s teshuva was adopted by the CLJS, Rabbi Amy Eilberg dissented, saying that although creating a way for shut-ins and others who are remote from a synagogue to participate is a worthwhile goal:

To offer a technological facsimile of a sheliach tzibbur (prayer leader) in place of a living, breathing, hurting, dreaming, praying leader and role model is a degradation of Jewish worship. It is a violation of Jewish beliefs about the holiness of God and humanity. And it is an affirmation of all that is worst in Conservative Jewish life: worship as vicarious experience, prayer as spectator sport, religion as theater, choreography and show rather than inner work and transformation2.

By 2001, the open Internet was in wide use, and Rabbi Avram Reisner prepared what has become the seminal teshuva on remote participation in weekday tefila. He drew on re-interpretation of classic sources, including the Shulchan Arukh (55:13) dispensation that if faces can be seen, a minyan may include persons outside a window. R’ Reisner held that, while a minyan may not be constituted over the Internet, if a minyan is present in a single location, others may fulfill requirements such as saying mourners' kaddish or kedusha from a remote location through an electronic connection. He reaches this conclusion reluctantly, saying,

Only in rare or exigent cases, with regard to shut-ins and hospital patients, those traveling or simply resident in distant parts, in hurricane or blizzard conditions, is the advantage of this use of distant-connection to the minyan compelling….It is only in those extraordinary conditions that we imagine its use3.

In his extensive (and contested) 2012 analysis of the use of electricity on Shabbat, Rabbi Daniel Nevins finds that if systems are set to operate automatically, and if there is no recording made, it may be possible to broadcast prayer services on Shabbat4: “We must acknowledge, however, that for some people who are physically isolated, it is not possible to “make Shabbat” with others. For them, telecommunications may be the only avenue for connecting with friends and family and even for participating in Torah study or communal prayer.”

Entering the Pandemic

So Conservative Jews began the COVID era with the teachings that while not desirable, one may fulfill mitzvot of tefila joining remotely when circumstances demand it; it is not possible to be counted in the minyan joining remotely; and it is not permissible to manipulate electronics on Shabbat. Then, with COVID threatening wide-scale disease and death, many of our rabbis declared a she’at hadehak and scrambled to interpret how that might best be understood in this era of Internet communication technology.

Atlanta Rabbi Joshua Heller has been an important voice leading these interpretations. In May 2020, he drafted the first teshuva on streaming services in the pandemic era. It holds for the sake of pikuah nefesh (protection of human life) in a time of she'at hadehak, it is allowable to form minyanim by counting persons who join electronically -- with certain requirements, including the need that each person be seen and heard by the community, as well as restrictions concerning leyning Torah and hearing shofar5. The requirement to be seen and heard in order to be counted is why we used Zoom technology the first year of COVID, rather than livestreaming, and why we continue to do so in weekday services. R’ Heller is less sanguine about using these technologies on Shabbat, offering that livestreaming is possible without manipulation of electronics on Shabbat, yet warning that “encouraging large numbers of Jews to spend more time in front of a screen on Shabbat can have a deleterious effect on the atmosphere of Shabbat.” He also raises questions he doesn’t answer, including whether Torah reading and aliyot may take place remotely. Finally, Heller forecasts continual future changes in communications technology and suggests that continual revisiting of these questions will need to take place as those changes occur.

Not all Masorti authorities agree with these prescriptions, including R’ David Fine who thinks even livestreaming comes with too great a temptation to “write” by copying bits of the transmission onto one’s own computer6. R’ Amy Levin, suggested that there are other ways to maintain our prayer communities without violating Shabbat proscriptions, including promoting small prayer groups, and Zoom teaching and prayer before Shabbat and hagim and afterwards7. R’ David Schuck offered the pandemic could have led us to “[seize] upon this moment as an opportunity to strengthen the skills and confidence of our members to “do Judaism” at home, to wit, become more Jewishy (s.i.c.) independent.”8

Over the past year, R’ Heller has explored the question of when we will know that the pandemic has ended. He suggests that some of the exemptions made during the pandemic may require something of a soft landing as the pandemic’s end date is not likely to be a hard line and given that some members of our communities are more susceptible to illness because of their own states of health9.

R' Heller also asks whether it is time to reconsider the limitation requiring ten Jews in the same physical space in order to constitute a minyan: “The assumption is that God’s dignity requires 10 Jewish individuals to be present if God’s full praise is to be offered. We must (and will) ask whether a virtual gathering creates this level of dignity.”10 Heller posed three options for congregational rabbis which he presented for CJLS votes. The first option, precluding virtual minyanim for most purposes but leaving open the weekday possibility of an exception allowing virtual minyanim only for the mourners' kaddish had nearly unanimous support. The second option of allowing special procedures to count a tenth when only nine are present was supported by a majority of the committee. The third option of a real-time hybrid minyan in which all can be seen and heard, but with restrictions on leyning Torah and other specifics, failed to get the support of a majority of the committee.

Among those who argue against continuing virtual practices for counting minyanim is R’ David Fine who says,

Overall, while there is a tradition of leniencies in the halakhic tradition to help a community “make a minyan,” they are all focused on the definition of physical proximity. To apply these leniencies to virtual distance, where there is clearly physical space in between the worshippers that is not included in the minyan, is an expansion of their application that, while perhaps suggested by new technology, is not by any means the only way to read those sources. One could just as easily, or likely more easily, read them as restricting a minyan to a space of physical proximity.

Rabbi Fine concludes that once the she’at dehak of COVID is over and we return to normal circumstances, the conclusion of Rabbi Reisner’s 2001 responsum is sustained: we should allow additional prayers to join a prayer service remotely, including recitation of kaddish, but we must not count them in the minyan11.

The renowned halakhic authority Rabbi Elliot Dorff, lends support to all four of the options given in the teshuvot just described by rabbis Heller and Fine, and argues that each of the four might legitimately be chosen by rabbis acting as the mara d’atra (decisor) of their congregations”:

[W]hen we do not know what the newly emerging realities of Jewish life will bring in each location, it is important for the CJLS to adopt the stance of humility articulated in Rabbi Tucker’s essay in recognition that the local rabbi will know best what, if anything, to do now in using the new technology to conduct services and whether to adjust that policy in the months and years to come12.

What do we do next?

So, there are a range of possible positions seen as potentially appropriate post-pandemic by Conservative rabbis, including livestreaming on Shabbat and Yom Tov, and livestreaming or Zooming on weekdays. All authorities agree that remote participants may fulfill their own obligations through virtual participation, but the most expansive interpretation on counting a minyan is that the remote participants may only be counted for mourners’ kaddish, or that the aron ha’kodesh or a pre-b’nei mitzvah child may be counted as a tenth if nine are physically present.

Rabbi Kaiman says he wants to have our next policies in place by Rosh Hodesh Elul (27 August). In preparation for those decisions he and our Religious Life Committee hope to hear from as many of you as possible. Thinking about the Conservative rabbinic positions on what is and is not acceptable, what choices do you believe Shearith Israel should make in order to strengthen our community and ensure a meaningful prayer life? Understanding the constraints, are you ready to commit to joining in-person prayer in our shul? Once the pandemic is really behind us, what is your vision for tefila at CSI.

B’shalom,

Baruch Stiftel and the Religious Life Committee (Lynne Borsuk, Sara Duke, Barry Etra, Mike Froman, Katie Levitt Green, Al Hazan, Ed Jacobson, Melanie Kaplan, Susie Mackler, Sarah Ossey, Edward Queen, Michael Rich, Andrea Seidel Slomka)

_____________________________________________

1. R’ Gordon Tucker. The use of a remote audio/video monitor on Shabbat and Yom Tov. OH 340:3.1989a. Rabbinical Assembly. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/teshuvot/1638976414.pdf

2. R’ Amy Eilberg. The use of a remote audio/video monitor on Shabbat and Yom Tov. OH 340:3.1989d. Rabbinical Assembly. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/assets/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19861990/eilberg_audiovideo.pdf

3. R’ Avram Israel Reisner. Wired to the Kadosh Borukh Hu: minyan via Internet. Rabbinical Assembly. OH 55:15.2001. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/teshuvot/1638962179.pdf

4. R’ Daniel S. Nevins. The use of electrical and electronic devices on Shabbat. Rabbinical Assembly. OH 305:18.2012a. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/ElectricSabbathSpring2012.pdf

5. R. Joshua Heller. Streaming services on Shabbat and Yom Tov. Rabbinical Assembly. OH 340:3.2020a. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Streaming%20on%20Shabbat%20and%20Yom%20Tov%20Heller.pdf

6. R’ David Fine. Streaming services on Shabbat and Yom Tov: a concurring opinion with a note on Dukhening. Rabbinical Assembly OH 340:3.2020b. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/StreamingConcurrenceDavidFine.pdf

7. R. Amy Levin. “Streaming services on Shabbat and Yom Tov” – a dissent and a challenge. Rabbinical Assembly OH 340.3.2020c. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Streaming%20Services%20on%20Shabbat%20and%20Yom%20Tov%20Dissent-%20Levin.pdf

8. R’ David A. Schuck. “Streaming services on Shabbat and Yom Tov” – a dissent. Rabbinical Assembly OH 340:3.2020e. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Streaming%20Services%20on%20Shabbat%20and%20Yom%20Tov-%20A%20Dissent-%20Final%20Copy%20%281%29.pdf

9. R’ Joshua Heller. Are we there yet? The pandemic’s end and what happens then. Rabbinical Assembly HM 427:8:2021Ȣ https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/heller%20pandemic%20end%20teshuva%20%281%29.pdf

10. R’ Joshua Heller. Counting a minyan via video conference. Rabbinical Assembly. OH 55:14.2021a. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/heller%20-%20zoom%20minyan%20%282%29.pdf

11. R’ David J. Fine. A minyan is constituted in person. Rabbinical Assembly OH 55:14.2021b. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/fine%20-%20minyan%20in%20person.pdf

12. R’ Elliott Dorff. Concurrence with Rabbis Joshua Heller and David Fine. Rabbinical Assembly OH 55:14.2021c https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/dorff%20concurrence%20to%20heller%20and%20fine%20%282%29.pdf

2 Adar I 5782 / 3 February 22

My Torah reading journey

I read Torah for the first time at my Bat Mitzvah in 1983 and then again in preparation for my daughter Stella’s Bat Mitzvah in 2017, almost 30 years later! And since then I have also read at both of my sons’ bar mitzvahs as well as many times in between. I even read once at my nephew’s bar mitzvah in Chevy Chase, MD. Each time I spend hours preparing and am so worried I will not be ready, and then feel a true sense of accomplishment once I have finished. And it’s a pretty special feeling to be standing in front of the Torah and to look out on the congregation. But nothing is better than all the hugs and kisses and yasher koachs I get on the way back to my seat. And due to COVID, my parents in North Carolina have even been able to hear me read beyond at our family simchas.

I read Torah for the first time at my Bat Mitzvah in 1983 and then again in preparation for my daughter Stella’s Bat Mitzvah in 2017, almost 30 years later! And since then I have also read at both of my sons’ bar mitzvahs as well as many times in between. I even read once at my nephew’s bar mitzvah in Chevy Chase, MD. Each time I spend hours preparing and am so worried I will not be ready, and then feel a true sense of accomplishment once I have finished. And it’s a pretty special feeling to be standing in front of the Torah and to look out on the congregation. But nothing is better than all the hugs and kisses and yasher koachs I get on the way back to my seat. And due to COVID, my parents in North Carolina have even been able to hear me read beyond at our family simchas.

About a year ago, Baruch reached out to me to ask if I could help engage others who may be interested in learning to read Torah. I have had the fortune of connecting with a variety of our members, some who are old friends and I have made some new friends along the way. Several of our accomplished Torah readers volunteered to be teachers and we set about pairing up student and teacher.

Howard Zandman who has been reading for many years was paired with Andy Greene, who had read at his own Bar Mitzvah and, like me, wanted to read again as his son was nearing Bar Mitzvah age. I loved connecting with Andy and found out my 16 year old son is the madrich in his son’s Machaneh Shai class. Andy read in November and had the following to say, “Reading in the synagogue, participating directly in the service, was very meaningful and gave me another layer of connection with the ritual. But the process of learning the parsha and the trope, and working with Howard, was equally meaningful. He was a terrific teacher, patient, knowledgeable, and easy to work with. I am now working on another portion for March.”

Katie Greene (no relation to Andy) is another new Torah reader. She worked with Erin Chernow who has taught so many of us to read Torah, including myself. Katie said, “Reading Torah for the first time since I was a teenager is equal parts scary and invigorating. As an adult you're making the choice to do this (rather than it being a requirement for a Bat Mitzvah), so being that it's an intentional commitment makes the learning that much more fulfilling. Erin Chernow has been a godsend to work with and I'm frequently in awe of her clever approaches for tackling the nuances within the readings.”

It’s a warm feeling to have so many congregants that are able to read Torah - one of the many things that makes Shearith Israel such a special place for all of us. And we are all welcome to learn, from those that cannot read a drop of Hebrew to those that have read before but need a refresher. Please reach out to me if you are interested in joining this wonderful group of Torah readers.

A forever student of Torah reading,

וּקְשַׁרְתָּ֥ם לְא֖וֹת עַל־יָדֶ֑ךָ וְהָי֥וּ לְטֹטָפֹ֖ת בֵּ֥ין עֵינֶֽיךָ׃

וּקְשַׁרְתָּ֥ם לְא֖וֹת עַל־יָדֶ֑ךָ וְהָי֥וּ לְטֹטָפֹ֖ת בֵּ֥ין עֵינֶֽיךָ׃

And you shall bind them for a sign upon your hand and let them serve as a symbol between your eyes.

9 Shevat 5782 / 11 January ‘22

You probably started learning the pasuk of Devarim (6:8) that is the reason we wear tefillin as a toddler, but you may not have given it much thought. Or, you may have questioned whether the black, leather boxes and straps were really what was intended when the pasuk was first written.

Amulets have a very long history, with evidence of use going back 25,000 years, so perhaps it is not unexpected that Jews would concretize core words of Torah in physical form for daily wear. Inscribed on the parchments in every tefillah are Shemot 13:1-10, Shemot 13:11-16, Devarim 6:4-9 (the Shema’s first paragraph), and Devarim 11:13-21 (the Shema’s second paragraph). The four excerpts state our belief in HaShem, our bond of love with HaShem, and our obligations to remember the Exodus and to teach our tradition to our children.

It seems likely that wearing of tefillin, or something like them, predates the Torah. The Torah commandments about tefillin are sparse, as if much is assumed. Then there is the talmudic discussion of HaShem showing Moshe his back in Shemot (33:21-23): “What did Moses see when He beheld God’s back? “Rav Chana bar Bizna said in the name of R.Shimon Chasida: ‘This teaches that the Holy One, Blessed be He, showed Moses the knot of tefillin’”.1

Tefillin are said to help us remember the covenant and our obligations, to subject our hearts’ desires and the faculties of our minds to the service of HaShem.2 The short prayers recited when wrapping tefillin include the symbolism of marrying HaShem: “I will betroth you to me forever. I will betroth you with righteousness, with justice with love and with compassion. I will betroth you to me with faithfulness, and you shall love the Eternal.”3 A Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs brochure explains, “When we wear Tefillin we bind ourselves to the highest spiritual level and achieve a closeness to G-d that even the deepest meditation cannot accomplish.” That brochure goes on to cite regular users of tefillin as likening them to a bandage, as bringing comfort, as if HaShem grasps your arm, holds on to you and says, “You can do this. I’m with you. I’m supporting you.”

Tefillin are worn for shacharit prayers on weekdays; not on Shabbat, Rosh HaShanna, Yom Kippur, or festivals, the principle being that those holy days are themselves reminders of the mitzvot. On the Tisha b’Av fast day, tefillin are worn in the afternoon mincha service instead of the morning shacharit. It is common to kiss tefillin with fingers during the Ashrei and Shema prayers.

While laying tefillin once was the norm, many in liberal Jewish communities have lost the practice. Those who did not learn it as children or teens may find laying tefillin awkward. While there are historic precedents to women’s use of tefillin, few women followed the practice until the most recent decades, and still there are few female role models for the new generation.

Tefillin were the archetype of time-bound mitzvot from which women were exempted in Talmud. The Conservative/Masorti view of this exemption has undergone radical reformulation in the past half century. In 2014, a landmark teshuva written by Rabbi Pamela Barmash and adopted by the Rabbinical Assembly’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards holds that, “Women are responsible for the mitzvot of reciting the Shema and the Shemoneh Esreh, wearing tzitzit and donning tefillin, residing in a sukkah, taking up the lulav, hearing the shofar, counting the omer, and studying Torah.”4

On Sunday, 13 February, CSI will participate in the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs’ World Wide Wrap. Machaneh Shai sixth graders will join congregants in a morning prayer service with tefillin celebrated across the USA and abroad by hundreds of Masorti congregations. Background on the WWW and instructional videos on laying tefillin may be found on the FJMC website. Please consider joining this spirited service.

In the interest of encouraging broader use of tefillin, Shearith Israel is launching a B’nei Mitzvah Tefillin Challenge. The shul will give a pair of tefillin (paid for from the Kornblum Minyan Fund) to new CSI b’nei mitzvah who attend a class in the mitzvah of tefillin taught by Rabbi Kaiman, and who pledge to attend and lay tefillin at at least ten weekday and/or Sunday morning minyanim at Shearith in the year following. This year, older CSI teens will also be eligible to participate. There will also be opportunity for adults to purchase their own tefillin at the shul’s negotiated bulk purchase price. Details of the challenge will be announced in the next weeks.

Kol ha’Kavod,

Baruch Stiftel

1. Babylonian Talmud, Berachot 7A.

2. Shulchan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 25:5

3. Hoshea 2:21-22

4. Rabbi Pamela Barmash. Women and mitzvot. Rabbinical Assembly, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. Y.D. 246:6, approved April 29, 2014.

28 Tammuz 5781 / 8 July ‘21

Is it meaningful to recite a half hour of difficult text in a language most of us don’t understand?

I chanced on a commentary on this week's parashat Mattot from a third century Rabbi Ami of Tiberias. He points to the list of nine towns east of the Jordan mentioned at the beginning of Chapter 32, when the leaders of Reuben and Gad ask Moshe to let them remain in Transjordan rather than enter Canaan. R' Ami uses the nine towns to make the point that we should study the weekly parasha thoroughly in the week prior to its public reading – both in Hebrew and in our vernacular -- even including a clause like the nine place names, since nothing in Torah is superfluous.1

R' Baruch Halevi Epstein (19th- 20th Centuries, Lithuania) points out that the nine place names seem to add nothing to the narrative, and yet we are to study them since, "Everything is equally sacred in the Torah."2

This is the basis taken by R' Ismar Schorsch, the long-time chancellor of JTS, to say: "We are no longer able to identify the human and divine strands in this dialogue, yet there is nothing that is not capable at some point in our lives to erupt with transcendent meaning. This is why we read it all. To select only that which we fatham at the moment precludes growth. By wrestling sequentially with the unexpurgated text each year, we allow life-experience, new knowledge, and outbursts of imagination to illuminate ever more swaths of darkness. To read seriously makes us part of an ageless conversation."3

Schorsch goes on to emphasize that the quality of the reading in synagogue is vital; that solid preparation, and reading of the full kryiah are essential if we are to connect our lives with the text. He calls for mobilizing the young Jews in our midst to become a cadre of expert Torah readers, for continuous personal study, and for proficient Torah reading to elevate our services spiritually.

I relay these commentaries because CSI is at something of a crossroads. With generational change it has become harder to fill the eight weekly leyning slots each Shabbat, plus the three weekday readings. Our corps of regular leyners are of enormous value to this community. They are supplemented by a few dozen others who read occasionally. Six of our congregants stepped forward this spring to advance their leyning skills through partner study -- and six others are coaching them. Torah reading is a great responsibility, but it is also a great privilege. To honor the aspirations of rabbis Ami, Halevi Epstein and Schorsch; to bring our life experiences to the text; and to continue the full weekly kryiah in our public reading, will require this group and others. It also calls on each of us to take time with the text during the week, so we are ready to extract the most meaning from the public reading.

Tihyu bri’im / Be well,

Baruch

1 Bavli Berachot 8a

2 Tosefta Megillah 3:20

3 Ismar Schorsch. “Let us return to a full Torah reading,” Pp. 575-578 in Canon Without Closure: Torah Commentaries. Aviv Press, 2007.

29 Iyar 5781 / 12 May 21

“A mahzor that can really address people in a heartful place”

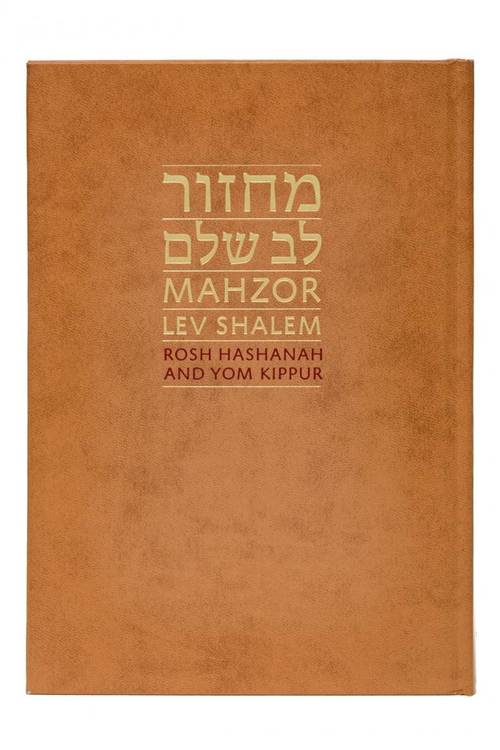

Shearith Israel will daven from a new mahzor beginning this coming Rosh HaShannah. We are switching to Mahzor Lev Shalem, published by the Rabbinical Assembly, to appeal across the spectrum of Conservative Judaism from traditionalists who want every bit of ageless liturgy, to post-modernists who want relevance to contemporary life.

Lev Shalem includes most traditional piyutim and m’sheberach prayers. It utilizes a 21st Century Masorti approach to gender, including a matriarch option in the Amida and avoiding male pronouns when referring to HaShem. There are aids to reading Hebrew, including differentiating kamatz katan from kamatz gadol. The English translation has a contemporary feel, yet takes care not to mask meaning. There are cues for standing, sitting, bowing, etc., not unlike what some of us know from Art Scroll siddurim.

The biggest innovation in Lev Shalem, however, is its commentary. Almost every page has readings or meditations that provide context and stimulate reflection. Some of these are from ancient sources; others are contemporary, including authors as diverse as Reuven Hammer, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Lawrence Kushner, Nina beth Cardin, Bahya ibn Paquda, Nahman of Bratzlav, and death camp survivors. The result is both a prayer book and a guide to Jewish thinking and experience of tefila, teshuva and tzedaka. Here is a sample: https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/public/jewish-law/holidays/mls/mahzor-kol-nidrei.pdf

The biggest innovation in Lev Shalem, however, is its commentary. Almost every page has readings or meditations that provide context and stimulate reflection. Some of these are from ancient sources; others are contemporary, including authors as diverse as Reuven Hammer, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Lawrence Kushner, Nina beth Cardin, Bahya ibn Paquda, Nahman of Bratzlav, and death camp survivors. The result is both a prayer book and a guide to Jewish thinking and experience of tefila, teshuva and tzedaka. Here is a sample: https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/public/jewish-law/holidays/mls/mahzor-kol-nidrei.pdf

In Rabbi Jan Uhrbach’s words, “Mahzor Lev Shalem is a book everyone will be able to enter; that will allow people to come to the moment of prayer with a whole heart.” There is something here for everyone.1

This switch began with discussions of the Avodah Task Force during CSI’s Strategic Planning process two years ago. Then Rabbi Kaiman and the Religious Life Committee delved into the details, including seeking opinions from rabbonim and lay members at other synagogues using Lev Shalem. Ultimately, the shul’s Board of Trustees made the decision to switch this winter.

Financing 900 copies of a new mahzor is a substantial undertaking. To help pay the cost, we are making copies available to members for purchase and also asking that members consider donating to dedicate copies of Mahzor Lev Shalem in memory or in honor of loved ones. To purchase or donate, please go to this web page: https://www.shearithisrael.com/mahzor-lev-shalem.html

Solomon Schechter famously said, “at a time when all Jews prayed, one prayer book sufficed their needs. Now when far less Jews pray, more and more prayer books are required.”2 Mahzor Lev Shalem is a remarkable effort to show Schechter wrong. This one prayer book guides, teaches and motivates widely throughout the Masorti world, and will similarly serve the broad tent that is Shearith Israel.

Lehitra’ot,

Baruch Stiftel

2. Quoted in Robert Gordis. A Jewish prayer book for the modern age. Conservative Judaism. 2 (1, 1945): 1.

25 Shevat 5781/ 7 February 21

.המקום ינחם אתכם בתוך שאר אבלי ציון וירושלים

Ha’makom yenachem etkhem betokh she’ar avelei Tziyon v’Yerushalayim.

May G-d console you among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem.

We have had eleven deaths in our kehilla in the 34 days since the start of the Gregorian year. I don’t know how many resulted from COVID, but I know this is more death than we usually would see in such a short time. Each day in minyan there are mourners in shiva, in sheloshim, and saying kaddish for 11 months. The sight and sound of them is both warming and jarring. I remember my own mourning and my own parents, and like others in the minyan, I try to reach out to comfort as best I can.

I was a young man in my second year of a steady income when my father, may peace be upon him, died. During the shiva week, my uncle accompanied me to minyan one afternoon. Sitting in the beit midrash waiting for the service to start, I told him that I felt something of an imposter, that I wasn’t an attentive, observant Jew, and here I was davening during shiva as if I was. Uncle Alfred looked at me with a kind smile and said that what mattered was that I was there, especially that was what mattered to my dear father.

Back then, Rabbi Maurice Lamm’s The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning1, introduced me to our rituals and practices, which I tried to follow as best I could. It was immensely comforting to have a roadmap. I was filled with grief and unsure of the future, fearful for my widowed mother, and in a new city. Shiva wrapped me in a blanket of warmth, left no doubt of the family love surrounding me. Then, kaddish helped me build a community in my new city, actually a community that transcended my city. When I traveled that year, there was always a minyan, and likely as not minyanaires who inquired after my loss and offered to share a few moments over breakfast or coffee. I had many conversations in which I imagined talking with Abba that helped me figure out quite a bit about him and me. By the time Abba’s first yarzheit came around, I wasn’t done grieving, but I was prepared to move on with my life.

Sharing time with so many new mourners now, I looked again for Lamm’s book. By chance I found his more recent, Consolation: The Spiritual Journey Beyond Grief2, in which Rabbi Lamm argues that most people only want to get through mourning and back to regular life, while it is possible for grief to lead to healing, increased self knowledge, and growth. Lamm shows convincingly how the rituals of Jewish mourning encourage this, and attempts to guide those of us surrounding mourners how to encourage these outcomes, while firmly insisting that there is no consolation without the intervention of HaShem. Lamm quotes the South African John Welch: “With my tears I would water roses, to feel the pain of their thorns and the red kiss of their petals” (p. 8).

Tradition dictates that burial of the dead takes precedence over almost all other activities, even the Kohein Gadol is instructed to leave his path on Yom Kippur to ensure burial of the dead. At Shearith, notice of a death draws the immediate attention of office, rabbi, Chevra Kadisha, Cemetery Committee, and Chesed Society, although each is now challenged by the pandemic. Rabbi Kaiman will be at the virtual bedside of the deceased offering advice and comfort to the onenim (mourners between the time of death and internment). Before COVID, the Chevra Kadisha would have washed and prepared the met/meta (body) for burial. Instead, in this time of COVID, actual preparation of the met/meta is carried out by funeral home personnel, while Chevra members recite prayers focused on the sacredness of the moment. They ask the deceased for forgiveness for any indignity they may have caused; they call on HaShem to have mercy and compassion on the deceased and to validate that, just as the deceased was created in the image of G-d, so too do we recognize the beauty of the neshama of the deceased. Chevra members also talk with the met/meta’s neshama that is believed to hover over the met/meta prior to burial. The Cemetery Committee is available to secure a burial plot if the family wishes burial in a Shearith Israel cemetery. The Chesed Society is on the phone with the onenim, offering a seudat havra’ah (meal of resuscitation) to follow the levaya (burial service). Then, if the wishes of the family allow, our community surrounds the mourners virtually at the levaya, and join them in shiva visits, these days most often online.

The days and months that follow reflect the personalities and circumstances of the aveilim (mourners), but as a community we want to wrap them in comfort any way we can. There can be visits, phone calls, assistance with responsibilities. The right words don’t come easily, but one’s presence speaks loudly. “G-d performs a miracle for every mourner who accepts the medicine of consolation given him by others, and in that way he heals them from the anguish of grief.”3

For many aveilim, this is the first time in their lives they have prayed with a minyan on a regular basis. For some, the rhythm of daily prayer gives structure to their routines. Some become motivated to learn to lead services. All find a concerned group of friends who want to be supportive in whatever ways they can.

Lamm suggests that the experience of death of a close loved one can change one’s view of G-d. Still, the rituals we practice require no specific theology. They reflect an acute, if ancient, understanding of human psychology and benefit from the instincts of love. It is as if the rest of us in the community become stronger and closer as we take some of the burden of grief off the shoulders of the aveilim.

.הַזֹּֽרְעִ֥ים בְּדִמְעָ֗ה בְּרִנָּ֥ה יִקְצֹֽרוּ They that sow in tears shall reap with songs of joy. (Psalm 126:5)

B’shalom,

Baruch Stiftel

15 Tammuz 5780 / 7 July 20

ZOOMING TOWARD KEVA AND KAVANNA

There was a moment in March when everything upended in our country and along with it, our shul. With Coronavirus numbers rising at startling speed, song-filled gatherings understood to be a primary way for the virus to spread, and many religious communities moving to online services, rabbis of the Rabbinical Assembly (RA) struggled with what advice to give congregations. The Conservative Movement’s long-standing position has been that a minyan cannot be constituted by counting daveners who join by electronic means, although if a minyan exists in a prayer room, then others can participate by joining electronically.1 This post explains how we got from there to daily online-only minyanim and makes suggestions for getting the most from them.

March was a crisis situation. If Jews continued to gather for prayer, lives would be lost, perhaps many of them. On March 17, the chair and co-chair of the RA’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) released an advisory declaring that the dire circumstances of COVID-19 justified a more lenient position on constituting a minyan. Relying on the ancient themes of she’at ha’dehak – extraordinary moment --, and pikuah nefesh – safeguarding life --, R. Elliott Dorff and R. Pamela Barmash wrote:

“Some of us hold that in an emergency situation such as the one we are now experiencing, people participating in a minyan that is only online may recite devarim shebikdushah, prayers that require a minyan, with their community. The participants counted for the minyan must be able to see and hear each other through virtual means and be able to respond “amen” and other liturgical replies to the prayer leader.”2

In this crisis situation, and with Conservative/Masorti rabbis everywhere moving to allow online prayer services, R. Kaiman sought support of CSI’s Executive and Religious Life Committees and decided that our minyanim would move online both on weekdays and Shabbat/Yom Tov.

Two long months later, the CJLS issued a responsum examining the many halachic questions involved in using electronic Internet communication for prayer services on weekdays and on Shabbat and Yom Tov. In the responsum, R. Heller and colleagues recognize the she’at ha’dehak and the need for pikuah nefesh at the present time, and at length work through considerations of Shabbat violation and larger communal considerations. They conclude that it is permissible in this crisis moment, to conduct online services on weekdays and on Shabbat and Yom Tov. They express a preference for minyanim in which ten Jews are present in the prayer room, yet allow the possibility of counting the minyan using Internet participants. They prefer arrangements that do not require manipulation of electronic equipment: so livestreaming is preferred to web conferencing, but they allow the possibility of web conferencing.3

Shearith Israel has had a learning curve in Zoom, the software we use to facilitate our web-conferenced services. While services have taken place every morning and evening since mid-March, it was a few weeks before we mastered the scheduling and “choreography” necessary for these to flow smoothly. Weekly Torah study has been an important part of Shabbat morning services. We’ve come to understand that communal singing is near impossible across the Internet. Yet, we found ways to include Torah reading in our services, and have called three young women to Torah as b’not mitzvah. To the surprise of some, attendance has often been equal to, or in some cases goes beyond, what we were used to in in-person services. There are some families who have not made the switch to online prayer, some for halachic reasons and some because of the technology needed. On the other hand, we’ve enjoyed the regular participation of some new members of the minyan who join from other states, and in two cases, even other countries.

As the shul discusses re-opening scenarios, and as we plan for this fall’s High Holidays, it might be useful to review a few of the lessons we’ve taken from the three-month experiment so far.

While there is a temptation to view a prayer service on a computer screen much like a TV show, it is important to think of it as “going to shul”. Dressing in shul clothes, sitting in a situation that allows good posture, standing and sitting at appropriate times, all help reconstruct the atmosphere of the beit knesset (sanctuary) and help us achieve a sense of kavanna or intention.

The computer microphone creates a window into our homes. Muting our microphones when we are not addressing the gathering is a fundamental of web conferencing that is vital for prayer services. Background noises like children playing, lawn mowers, and trash trucks are magnified by the condenser microphones on computers. Even whispers can sound like shouting. Each service has a designated “Zoom host” who is charged with muting any sources of noise that are coming through. The host cannot unmute you, however, so we want participants to unmute themselves for portions of the service that require a congregational response, such as for the kaddish, the borchu, and the kedusha. A headset or earbuds can help reduce the chances of feedback when your microphone is on.

Finally, it’s useful to think ahead of time about the way one appears to the Zoom screen. If there is a bright light behind you, your face may not be visible to camera. Better to have room lights in front of you, not behind. And, check out how you appear in your Zoom tile when seated and when standing. We’d like to see your face; some other parts, um, less so. You can use the CSI prayer Zoom room off hours to test out these adjustments.

In these perilous times, our shul is trying to assist member families in every way possible. Educational, social, charitable and pastoral missions have continued, each in its own COVID-unique way. The form of personal prayer is one aspect of Jewish life that perhaps needn’t change much at all in these pandemic circumstances. But, communal prayer has become something very different. Despite the challenges, your rabbi, shul staff and lay prayer leaders have worked hard in the hope of helping you retain keva, routine, and kavanna, sense of intention, in your communal prayer. If you haven’t tried the online prayer services, I hope you’ll give them a try. You’ll be surprised at how well they support spiritual moments.

L’ chaim!

Baruch Stiftel

1. R. Avram Israel Reisner. Wired to the Kadosh Barukh Hu: Minyan via Internet. OH 55:15.2001.

https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Reisner%20-%20Internet.pdf

2. R. Elliot Dorff and R. Pamela Barmash. CJLS Guidance for Remote Minyanim in a time of COVID-19. 17 March 2020.

https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/story/cjls-guidance-remote-minyanim-time-covid-19

3. R. Joshua Heller. Streaming Services on Shabbat and Yom Tov. OH 340:3.2020a.

https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Streaming%20on%20Shabbat%20and%20Yom%20Tov%20Heller.pdf

8 Nisan 5780 / 2 April 20

MATRIARCHS IN THE AMIDA

On Shabbat before we temporarily stopped in-person communal prayer, a long-time Shearith Israelite asked me when our shul would move to always using the Amida text that names the Imahot (Matriarchs): Sara, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah; as well as the Avot (Patriarchs): Avraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

It is now eighteen years since CSI joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, and sixteen years since women are counted in our minyanim. While our siddurim provide two alternatives for the first two brachot of the Amida, and each of us decides for ourselves which one to use in our personal or silent prayers, for the past six years, we have looked to the sheliach tzibbur, the prayer leader, to decide whether to use the alternative text naming the Imahot in the public repetition of the Amida.

The reasoning in favor of including the Imahot is powerful. The Matriarchs were vital to the evolution of early Judaism, taking decisive action that changed the course of our history again and again. In making the decision to become egalitarian, our movement and our shul have responded to the dramatically changed roles of women in 20th - 21st Century western society. Language and literature have been rapidly changing to reflect these changing roles as well as to correct the frequent omission of women in our acknowledged history. The Rabbinical Assembly permitted approved text including the Imahot for the Amida in 19901.

Jews have been very slow to change liturgy, much of which goes back almost 2500 years. Phillip Birnbaum wrote in the introduction to the time-honored siddur he edited:

Editors of the Siddur should not take liberties with the original, eliminating a phrase here and adding one there, each according to his own beliefs. Such a procedure is liable to breed as many different kinds of public worship as there are synagogues and temples. The danger of rising sects is obvious, sects that are likely to weaken still more our harassed people2.

Despite the reluctance to change, our Siddur Sim Shalom, embodies a small number of significant changes from the ancient liturgy. We add the word בעולם (b’olam – universal) that does not appear in traditional liturgy, in praying for peace at the end of the Amida: “Grant universal peace.” Less obvious perhaps is the omission of וְאִשֵּׁי יִשרָאֵל (v’eeshay Yisrael - fire offerings of Israel), from the Shabbat Amida in the Avodah blessing, and the removal of the phrase, שֶׁהֵם מִשְׁתַּחֲוִים לְהֶבֶל וְרִיק וּמִתְפַּלְלִים אֶל אֵל לא יושִׁיעַ , (shahem mistahaveem l’hveil v’req, u’mitphal’lim ail ail lo yo’sheah - for they bow to vanity and emptiness and pray to a god which helps not), from the Aleynu prayer; both of which were changes made in the Morris Silverman edited siddur that Conservative shuls used for half a century prior to launch of Siddur Sim Shalom.

As of now, we are voting with our words, and with the words of our shelichei tzibbur. While each of us chooses to voice the Imahot or not in our private prayers, those who lead our services are making this choice in our public prayers. I have no doubt that the winds of change are upon us and in time we will move to uniformly include the Imahot. Need I point out that, if this is important to you, you can help it along by volunteering to lead services; then you will get to choose.

Wishing everyone a sweet, Kosher, and safe Pesah!

-Baruch

- Rabbi Joel E. Rembaum. “Regarding the inclusion of the names of the Matriarchs in the first blessing of the Amida.” Responsum adopted by the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, 3 March 1990. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/assets/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19861990/rembaum_matriarchs.pdf

- Philip Birnbaum, ed. Daily Prayer Book: Ha-Siddur Ha-Shalem. Hebrew Publishing Company: New York, 1949. P. xi.

26 Kislev 5780 / 24 December 19

SHEARITH ISRAEL’S RELIGIOUS LIFE GOALS

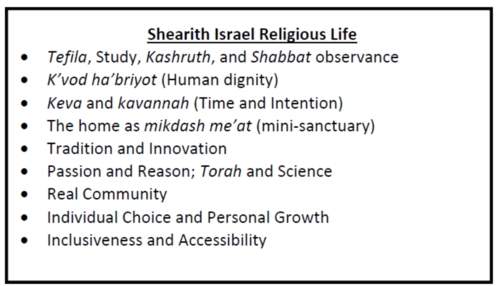

Last summer, deciding on tasks for the upcoming year, your Religious Life Committee was listing things like expanding the corps of prayer leaders (shelichei tzibbur) and updating the gabbai’si Rol-O-Dex Hebrew name files (Yes, we are still using Rol-O-Dex!), when Sarah Ossey asked what we were trying to achieve with all the tasks. So, the first item on the task list became, “Define goals for the Religious Life Committee”.

The ensuing process was exhilarating. All of us understood that prayer ritual is important, but writing down why and how to make it more so wasn’t obvious. It took us six months. Here is the result:

The first thing I hope you’ll notice is that the goals don’t stop at the sanctuary’s doors. When the shul By-laws were revised in 2013, what had been the Ritual Committee was renamed the Religious Life Committee. The by-law drafters thought that the Committee, together with the Rabbi and subject to Board oversight, ought to be working to enrich member lives across a range of Jewish practices largely left unnamed. Our Goal Statement speaks about tefila (prayer), kashruth (dietary laws), and Shabbat observance. We’ve been busy with tefila, but you can anticipate that down the road, this Committee will work to help support congregant aspirations in the other two areas as well.

The goals also talk about the importance of the home as a mini-sanctuary (mikdash me’at). We know that the center of Jewish life is the home, so that to be successful we need to be devoting attention to resources to support what happens at home as well as in shul.

Then, as you look across the list, you will see goals that speak to values: k’vod habriyot (human dignity), keva (timeliness), kavannah (intention), a balancing of tradition and innovation, of Torah and science, of promoting our congregation (kehilla) as a real community, as well as individual choice, personal growth, inclusiveness and accessibility. Over the next months, I hope to share the Committee’s perspectives on these important dimensions of religious life. Today, just a bit about k’vod ha’briyot.

The goal of k’vod ha’briyot, literally respect for the people, asks that we commit to avoiding embarrassment. This might seem straightforward, but think about all the ways we assume certain beliefs, knowledge and practices in Jewish life, and how easy it is for someone who doesn’t share some aspect of these to feel out of place or embarrassed in a room filled with others whom s/he assumes do share the belief, knowledge or practice. Then, contrast such a situation with the need to respect the community (k’vod ha’tzibbur), to create a space where Jewish practices are honored and followed, and the members of the community can feel at home.

So, for instance, we have the expectation that electronic devices will not be used inside our shul buildings on Shabbat and Yom Tov. We place signs about this in prominent locations, and we describe the expectation in our paper handouts. As much as some would want the rule to be absolute, we know that visitors and some members of the congregation do not share this expectation, may not even know about it. Some of us politely ask them to stop when they take out a cell phone or start to video record portions of a bar/bat mitzvah service. Others might audibly “tszk-tszk”, or show a disgruntled facial expression. Over the years, on a few occasions, I have even heard strident criticism out loud. Yet, most of us would agree that a doctor on call should be able to answer his or her phone; many would agree that a parent should be able to take an urgent question from a baby sitter at home with a young child. K’vod ha’tzibbur asks that we enforce the device ban; k’vod ha’briyot asks that we do so in the most private and kind manner. Our Committee, responding to Rabbi Kaiman’s teachings, has taken the view that respecting those who join us in prayer, in celebration, in solidarity or in curiosity is a primary Jewish value and should always be in our minds.

Chag sameach Hanukah!

Baruch Stiftel

i The Aramaic word gabbai literally means ‘tax collector’. In synagogues, gabbai’im once had a role to bring donations to the shul from those fulfilling honors. The role today is something of a combination of pit boss and aide to Torah readers.

29 Av 5779 / 30 August 19

REFLECTING ON (AND THROUGH) OUR LITURGY

The Avodah Task Force raised the question of whether Shearith should switch to the new Rabbinical Assembly Siddur Lev Shalem. Lev Shalem brackets the liturgy with commentary and context. It has been adopted by many Conservative kehillot and is available as an alternative in others.

Membership chair Jaime Wender suggested in a recent post on the facebook CSI Member Exchange that laminated cards with alternative readings or prayer commentary in our sanctuary book boxes would be informative and interesting for visitors and regulars alike.

While these suggestions are under discussion, I want to call your attention to two resources immediately available.

First, Rabbi Kaiman will offer an 11-week class this year, Jewish Prayer Series: Getting our Head Around, Our Hearts In and Our Bodies Engaged on selected Thursdays from early September through mid-March. The classes are staged under groupings concerned with our heads (September), our hearts (November), our bodies (January) and Bringing it all Together (March). While the sessions will build on each other, participants are welcome to attend when they can even if they have not attended earlier sessions.

Second, Ohr Hadash: a commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals by Rabbi Reuven Hammer, zt”l, is available on the book cart at the sanctuary door. Ohr Hadash is a commentary built around the exact text of the siddur Sim Shalom. Each Sim Shalom page is surrounded by various comments and resources intended to help inform prayer, explain historical origins and relate to modern sensibilities and challenges. In Hammer’s words, “…at no time does the commentary conceal what is thought to be the plain meaning of the texts at the time they were written. At the same time, it offers other ways of looking at them….It also attempts to be inspirational….”

Rabbi Hammer, a Syracuse native who graduated from JTS, passed away this month in Eretz Yisrael, where he has lived since the 1970s. He was a founder of Kehilat Moreshet Avraham in Jerusalem, head of the Masorti Bet Din in Israel, and president of the International Rabbinical Assembly. His 1995 book, Entering Jewish Prayer, is perhaps the most widely read contemporary source on Conservative/Masorti thinking about our liturgy and tefila practices.

As a teenager I was taught that the siddur was a starting point for prayer, not the end point; that I was always welcome to depart from the liturgy to speak to HaShem in my own words and from my heart. I tried to relay this same message to our daughter as she was finding her way in shul. Rabbonim Kaiman and Hammer offer us wonderful resources to help both understand tradition and find our own words. I hope you’ll check them out.

I’ll end with a few of Rav Hammer’s words, “If we are willing to understand prayer as poetry rather than as literal prose, we may find great meaning in it. We should worry more about its effect upon us and less about its effect upon G-d.”

Kol tov,

Baruch Stiftel

29 Tammuz 5779 / 1 August 19

A PLAN FOR RELIGIOUS LIFE AT SHEARITH ISRAEL, 5779-5780

Your Religious Life Committee has set a seven-pronged plan for the upcoming year intended to recharge CSI’s tefilot. Here are the highlights…

Following Rabbi Kaiman’s leadership, we will foster a conversation to better understand what members want from religious life at Shearith Israel and then set goals to support this.

We will expand the corps of congregants that lead services, leyn from Torah, and read haftara. If you are interested in learning one or more of these skills or freshening them up, stop by our table at Say Chai at CSI on 18 August, or let Michael Rich or Andrea Seidel Slomka know.

We will work with Rabbi Kaiman to be sure that the shul’s approaches and thinking about kashruth, tefila, and Shabbat are well understood.

We will review the campus to be sure that members and visitors are not placed in situations that cause them to inadvertently compromise their own religious practices.

We will outreach to new and long-time members in a creative effort to engage more of us in weekday minyanim in ways that we find meaningful and enjoyable.

As the shul’s Strategic Plan comes into focus, we will work to implement the recommendations of the Plan related to Avodah.

We’ll be updating the way in which the shul provides congregant names and Kohein/Levi status information to gabbaim and shamashim so that these officers are best able to widely distribute honors and call olim correctly.

And, of course, we will continue the regular work of supporting tefila through organizing Torah leyners (thank you Andrea Seidel Slomka!); shelachim tzibbur, haftarah readers, gabbaim and shamashim (thank you Michael Rich!); High Holiday honors (thank you Ed Jacobson!); and to organize minyanim each morning and evening (thank you Lynne Borsuk, Michael Froman, Ed Jacobson, Barry Fuchs, Elliott Rich and the others who take on these responsibilities).

In future posts, I hope to share specifics about each of the seven prongs, and to introduce the committee members to you.

The message that came through to me clearly as the Committee prepared this plan is the fervent desire that Shearith Israel should support congregants in religious growth, in times of celebration, and in times of need, and that we should be a force for advancing the teachings of Torah in the broader community. The Committee has clear direction; please give us your ideas and your energy so that Kehillat Shearith Israel grows in impact across the community.

Baruch Stiftel, Chair

CSI Religious Life Committee

SPRING 2019

25 Adar II 5779 / 1 April 19

From your new Religious Life chair...

Haverim:

After Faith Levy asked if I would stand for election as Religious Life Committee chair at CSI, I spoke with quite a few of you about what you wanted for the future of prayer services in our shul, I checked with Barry Etra and Pia Koslow Frank, the chairs of the Kadima process to learn what the strategic plan data collection was saying, and I sat with Rabbi Kaiman to better understand his vision for our future. While what I learned reminded me a little of the old adage, two Jews, three opinions, there really were common themes.

Shearith Israelites love our egalitarian, traditional-leaning Conservative services, except those who want services to be more innovative, more musical, with more English. We love our lay daveners who lead with joy and ruach, not with a desire to perform, except when they struggle with the Hebrew, have trouble keeping the key, or fail to fully reflect the sex and age diversity of the congregation. We want more meditative moments in services, but we see the meditative preliminary prayers as boring. We love having children in the Beit Knesset, except when they won’t sit still and make it hard to hear. We love having twice-daily minyanim, except when we feel awkward about not knowing what’s going on.

In my thinking, I pit these challenges against those of other kehillot I’ve been part of in the past, most of which wished for these problems. As I’ve shared with a number of you, I think of my shul past as having two kinds of communities: consumer communities, and producer communities. The consumer communities were populated largely by congregants who took the shul for granted; wanted it to be there when they needed it, but seldom lifted a finger to make anything happen. The producer communities were populated by engaged, giving Jews, who rose to the occasion to lead services, cook kosher food, teach the religious school, and sit with the dead. I learned about producer communities in a small shul where there was little choice about how we would do any of this because we had to work with the limited skills of those involved and we had to contend with largely empty pews.

Shearith Israel has both consumers and producers in good numbers. For a Conservative shul our size, the number of our friends who have learned to daven from the amud or to leyn Torah is extraordinary. The corps of congregants who volunteer to comfort the grieved and the sick, to prepare the dead for burial and to manage our cemetery, as well as to join in the work of repairing the world makes me so very proud to be a Shearith Israelite.

So reflecting on the challenges we face, I think (now follow my eyes lifting slightly toward the heavens and my shoulders rising ever so slightly, one palm turned up)… I think we have problems good shuls want.

We want to serve Hashem well, but we often disagree how to do that. Isn’t that symptomatic of our namesake, Israel: “one who fights with Hashem.”

We are blessed with many volunteer service leaders, of varying ability and talent, who in some ways reflect the diversity of Hashem’s children. So rather than sit back and admire the artistry of a great hazzan, we are motivated to set the key for those around us, or even to step forward and learn how to do it ourselves so that it’s done “right”.

When the the noise of children at play diverts our attention, we may need to look deeper for our own kavanah, but we can be contented to be surrounded by the vibrant voices of the next generation of Jews enjoying being in shul.

We may feel awkward not knowing what is going on in minyan, but next to us is a friend that would relish the opportunity to answer a question, and once we understand the outline we can walk into any shul in any city in the world and feel at home.

We have good problems. Really they are ambitions we should be proud of. We won’t achieve them overnight, but we will make good progress this year and next, because we are a committed kehillah that cares about our spiritual life and our service to community, Judaism, and the world. I relish the chance to work with the other members of the Religious Life Committee these next years to move us forward in addressing these ambitions. We’ll be calling out for you; please step forward in ways you can to enrich religious life at Kehillah Shearith Israel.

B’shalom,

Baruch Stiftel